We are keen to receive review comments for our new paper which is now available for open peer review (pdf)

Michael Alder: UK food security – An analysis

Food security is one of the thirteen sectors listed in the government Critical National Infrastructure document. The government’#’s food strategy (GFS) published in June 2022 states the government will aim to maintain food production in the UK at current levels, around 60% of the food we consume, and obtain the rest from importation from a diverse range of sources. This paper examines the potential for maintaining the 60% level of production, particularly considering key factors such as loss of productive agricultural land, crop yields and livestock productivity, UK population growth and labour availability. An analysis of these factors suggests the 60% will be difficult to achieve and the UK could become more reliant on food importation. Food importation is analysed in more detail and in particular the vulnerability of supply from the sources identified. The paper concludes that importation of food will become increasingly difficult due to a number of factors, but primarily the effect of climate change on global food production. As a result of the analysis in the paper a number of conclusions and recommendations are made.

Submitted comments and contributions will be subject to a moderation process and will be published, provided they are substantive and not abusive. (Closed open reviews of GWPF publications can be found here).

Review comments should be emailed to: benny.peiser@thegwpf.org

The deadline for review comments is 10 June 2024.

The draft has been withdrawn by the author.

—————-

Max Beran

Stated loss of what CPRE term “farmland” to developers is trivial compared with the UAA (and the other areas quoted by the author for categories of farmland). Measured in thousands compared with millions. Perspective is clearly needed here but not provided. ”Developers” is often used in a pejorative sense as I suspect it is here given CPRE defaults setting, but development has end uses which surely can be socially desirable.

Loss of farmland is the number one preoccupation of this author and we could benefit from a tabulation, pie chart or whatever as visual aids to the numerous land loss statistics.

The author appears to be very uncritical of a number of his quoted sources that GWPF has learned to be sceptical of and is somewhat more accepting of climate scare stories than GWPF. Little evidence of personal research in the references and much of some rather dubious looking secondary sources. Table 4 and the comments on page 4 are in contradiction and pass without comment or reconciliation. I do not find the tone of final sentence of section C much supported by Tables 4 and 5.

We need an equivalent to table 4 for the global situation so we can better judge the severity of the risks set out on the bottom of page 3 and top of page 4.

What about the impact of social eating trends? I’m thinking of all these people who turn up their noses to protein on the hoof which presumably puts increasing pressure on winter protein supplies from plant sources. Is this where ALC grades 3b and 4 fit in?

Are there no correctives in prospect? Normally the (non fiscal) market adjusts when supply and demand get out of synch. Does this not apply to food security?

Is there any crossover between energy costs and availability and food security acting through the energy demands of food production and distribution. Energy appears here mostly as a land use competitor.

Page 7 – amplify impediments to resilience in food chain: logistical constraints competition

Soil carbon- I’m no expert but isn’t it extraordinarily difficult to increase SOC? A century of manuring at Rothamsted didn’t do much as I recall.

————–

John McLean

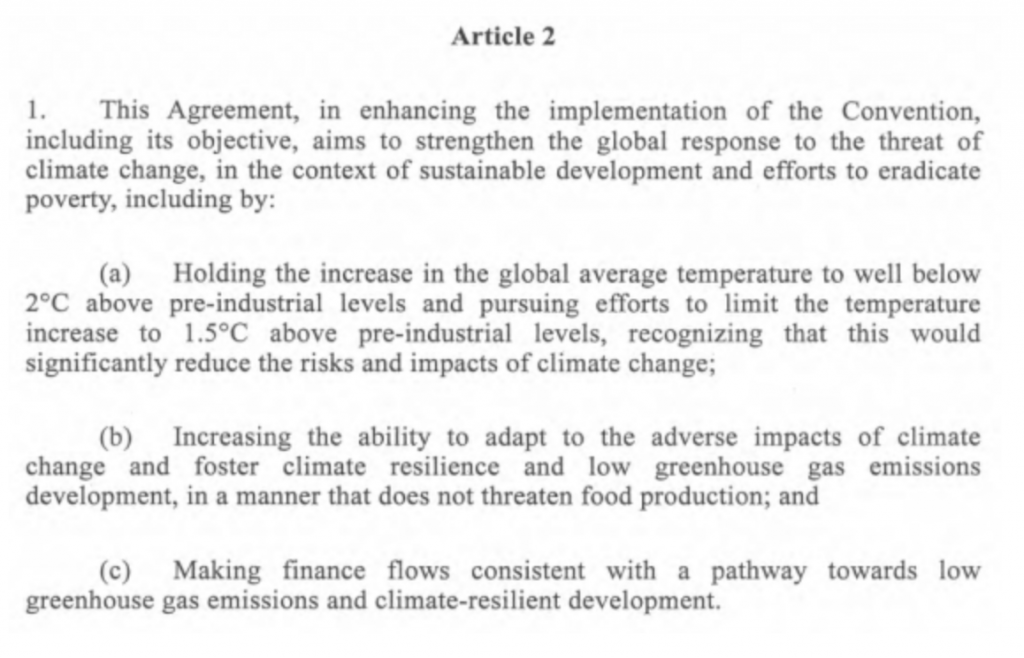

I see no mention of the Paris Climate Agreement in the draft document.

Here’s a snapshot of the relevant paragraphs. I draw your attention to the final few words of 1(b).

————–

Geordie Burnett Stuart

There should be a presumption against planning permission for solar farms on any of the 6 million acres of croppable land.

Peter Loxham

Considerable amounts of land having been turned over to wind farms (farms because they are harvesting the wind?) and solar farms (same definition, but sun). The government requirement for 10% land to be turned over to wooding, and 10% turned over to re-wildling, these plans alone removed potential land production from use.

The incredible facility that is Thanet Earth, Dover, is one way forward for our country’s food security. Wind and Sun are not this countries way forward for energy security.

We need to understand that farming, in all its forms, is the lifeblood of this country and whatever it takes financially to secure this vital resource will be welcomed by all.

—————

Andrew P Cullen Ph.D (Geography)

Draft paper summary

“The paper concludes that importation of food will become increasingly difficult due to a number of factors, but primarily the effect of climate change on global food production.”

Reviewer:

I did not find in the subsequent text convincing arguments or data to back this conclusion about the effects of climate change. I return to this point below.

DEFINITION OF FOOD SECURITY

Reviewer:

It is critical to take account of the fact that the 5 points elucidated to define “food security” in the Agriculture Act 2020, fail to include the economic health of the UK farming industry as a whole. This absence is unfortunately adopted throughout this draft paper.

If one looks at the Agriculture Act 2020, the first article sets out the powers given to the Secretary of State, and by extension to the Government’s bureaucrats (DEFRA), to intervene and interfere in the UK’s farming industry. This radical extension of the role of the REGULATORY STATE (DEFRA) into the farming sector, is dangerous and counter-productive; not least because it encourages and enforces centralised planning, and decision-making by a Government Department that is not fit for purpose to act in the best interests of farmers, farming and the rural economy.

Coming from a Conservative Government, the scope, variety and potential damage of these state interventions is astonishing. The new Act was a great opportunity to definitively be rid of the stranglehold of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy. Instead, it was used to massively extend the role of STATE INTERVENTIONS into UK farming.

The timing of the debates about this new 2020 Act coincided with Britain being in COVID Lockdown and subjected to massive extensions of State intervention into every aspect of the lives of the population. I posit that it is NOT BY CHANCE that the UK STATE exploited this opportunity to extend its’ reach into the Agriculture sector, since there was totally inadequate public debate and parliamentary scrutiny.

Four years on from the Act’s entry into force, the UK farming industry is now predictably in a parlous condition.

Pages 3 – CLIMATE CHANGE AND GLOBAL FOOD SUPPLY

Reviewer:

Key problems with the vast majority of public discussion about “Climate Change” are that:

(a) there is a failure to understand the distinctions between Climate Change and Weather.

(b) Since the start of the 21st century, the dominant narratives about “Climate Change” were financed, promoted and embedded into policy goals and international legislation by organisations like the UNO and the WEF, around whom powerful vested interests have coalesced and profited from subsidies and other benefits. With Corporate, NGO and State actors squatting the narrative, inevitably the unbiased evidence-based science is side-lined, and persona non grata to the titans of state power and financing.

However, the truth has a habit of re-emerging, because these dominant, but faulty, narratives are imploding under the weight of more evidence-based scrutiny and from the many acts of courageous testimony and research from independent scientific and other specialists.

Given the above, it is self-evident that all policy-related documents from official bodies and/or research entities funded by them, about “Climate Change” (aka Anthropomorphic Global Warming) need independent expert scrutiny in regards to their assumptions, data sets, conclusions and other potential biases.

The writer references four sources in this section to provide examples of food supply problems that “might affect” the UK. One is a report by the University of Minnesota with other universities, a document that is now TWENTY FOUR years old. The other three sources are from the UN (2019), the European Environmental Agency (2019), and the government of the Netherlands (2023). These three are all STATE ACTORS engaged in politics, climate alarmism, and erroneous thinking and policies about the impacts of CO2. In the case of the Netherlands government, there is full scale national conflict between the Dutch farmers and their government due to the coercion and expropriation that the latter under ex-PM Rutte were pushing through in the name of pursuing the anti-agriculture policy of “carbon capture”.

There is, in this reviewer’s assessment, only one vector of truth in these discussions of environmentally related food supply security to the UK: Soil erosion. Which, if left unaddressed may lead to desertification. Arguably, in agriculture, or at least in arable farming, the best custodians of top soil MUST BE the farmers themselves since soil is their foremost natural asset.

Page 4 – UK AGRICULTURE AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Extract

“Data from the Met Office20 confirms recent weather extremes. Some examples of these extremes are 2018, one of the hottest years on record, and 2019 one of the wettest”

20) Met Office data 2018-2023. November 2023.

Reviewer:

I may be mistaken, but is it not the case that it is precisely this report from the Met office that they had to revise/retract after receiving widespread push back from other data analysts? It is regrettable that the Met Office appears to be another organisation contaminated with wishful thinking.

Page 6 – CONCLUSIONS

Extract

“Managing extreme weather conditions must be central to UK food security policies.”

Reviewer:

I do not agree with this conclusion at all, as indicated by my comments above.

It is another example of bad conclusions from misrepresented data sets. Worse, could provide more excuses for counterproductive interventions by the state sector.

Page 7 –RECOMMENDATIONS

Extract

“ ii Protecting valuable farmland and developing a land use framework.”

Reviewer:

In principle this may be a “good idea”. The problems are ones of practicalities, implementation approach and risks AND ENSURING that entities like DEFRA and other NGOs and vested interests do NOT HIJACK it. A centralised approach will almost inevitably FAIL. The mentality of metropolitan bureaucrats is anathema to the needs of farming and rural economies.

Page 8 – “v. Agriculture research”

Extract

“The role of soils in carbon capture and storage and the development of sustainable land management practices are critical issues. (The World Economic Forum – WEF32 notes that increasing the carbon stocks by just 1% would capture more carbon than total annual global emissions from burning fossil fuels – a fact not often monitored by climate scientists).”

Given previous comments above about the negative and costly impact of governments and other organisations espousing the fictions of CO2 and climate change, the above recommendation is based on false climate science. It is now time to throw overboard the ballast created by the IPCC and their acolytes.

————–

Professor Gautam Kalghatgi

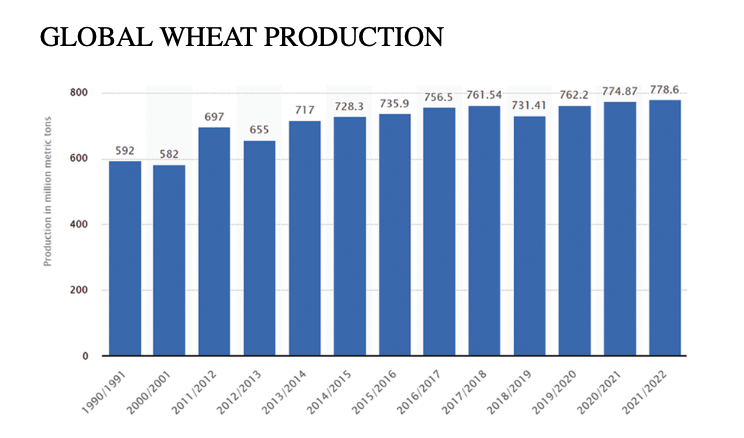

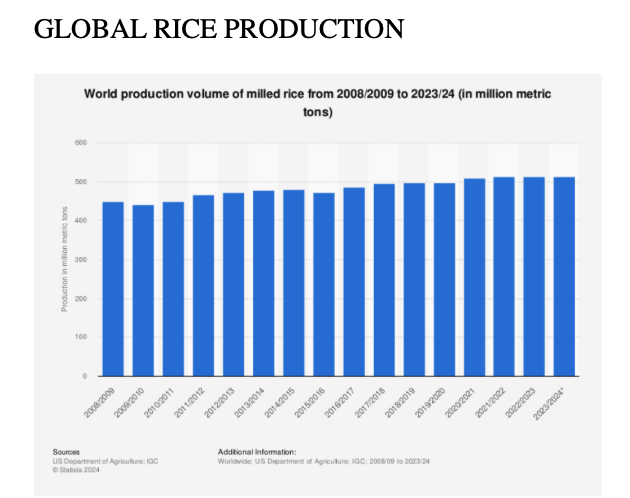

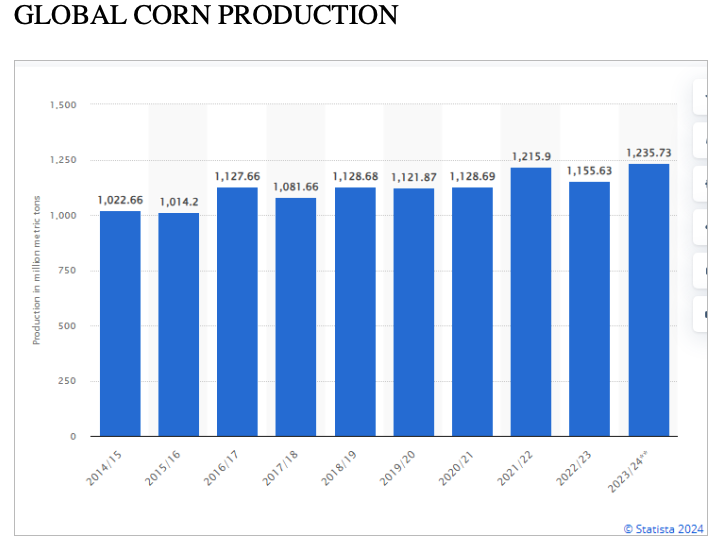

Further to comments by Andrew P Cullen, there has been an unbroken increase in food production and productivity over the past 60 years in spite of global warming as can be easily ascertained from multiple sources e.g., FAO data or from the excellent site – https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-production. This is the case globally or for individual countries like the U.K. or India. Incidentally, Indian government estimates for 2022-2023 again indicate record foodgrain production – rb.gy/g9vct6. Why should we expect future warming to reduce food production? If anything, increase in CO2 should increase food production as it has demonstrably increased global greening (e.g. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2016/carbon-dioxide-fertilization-greening-earth).

There is no statistical evidence (low confidence in IPCC parlance) that extreme weather events have increased in spite of global warming of the past. The IPCC findings are summarized here –https://rogerpielkejr.substack.com/p/how-to-understand-the-new-ipcc-report-1e3. As Roger Pielke says in that report, “..it is simply incorrect to claim that on climate time scales the frequency or intensity of extreme weather and climate events has increased for: flooding, drought (meteorological or hydrological), tropical cyclones, winter storms, thunderstorms, tornadoes, hail, lightning or extreme winds (so, storms of any type)”. So why should we expect that such events will get worse because of future warming?

Here are a few more relevant publications/papers which confirm that there is no evidence that severe weather conditions have got worse.

1. https://thegwpf.org/content/uploads/2021/02/Goklany-EmpiricalTrends.pdf – apart from severe weather, also looks at food production, poverty and other measures of human well being. See Tables 5 and 6 in the report.

2. https://thegwpf.org/content/uploads/2024/04/Humlum-State-Climate-2023.pdf – particularly chapters 8,9,10.

3. https://thegwpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Homewood-Hurricanes-2023.pdf – looks at hurricane data including 2023

4. Koonin, S.E. “Unsettled – what climate science tells us , what it doesn’t and why it matters”, 2021 BenBella Books Inc, Texas, Chapters 6 and 7.

5. A recent publication by GWPF (https://thegwpf.org/content/uploads/2024/03/History-Weather-Extremes.pdf) put weather extremes in historical context and refuted “the popular but mistaken belief that today’s weather extremes are more common and more intense because of climate change”.

————–

Dr John Carr

The paper is entitled UK Food Security, but also discusses global food production.The summary states: “The paper concludes that importation of food will become increasingly difficult due to a number of factors, but primarily the effect of climate change on global food production”. My comments question if climate change has really affected global food production. I find some sections of the paper unclear and make suggestions for clarifications.

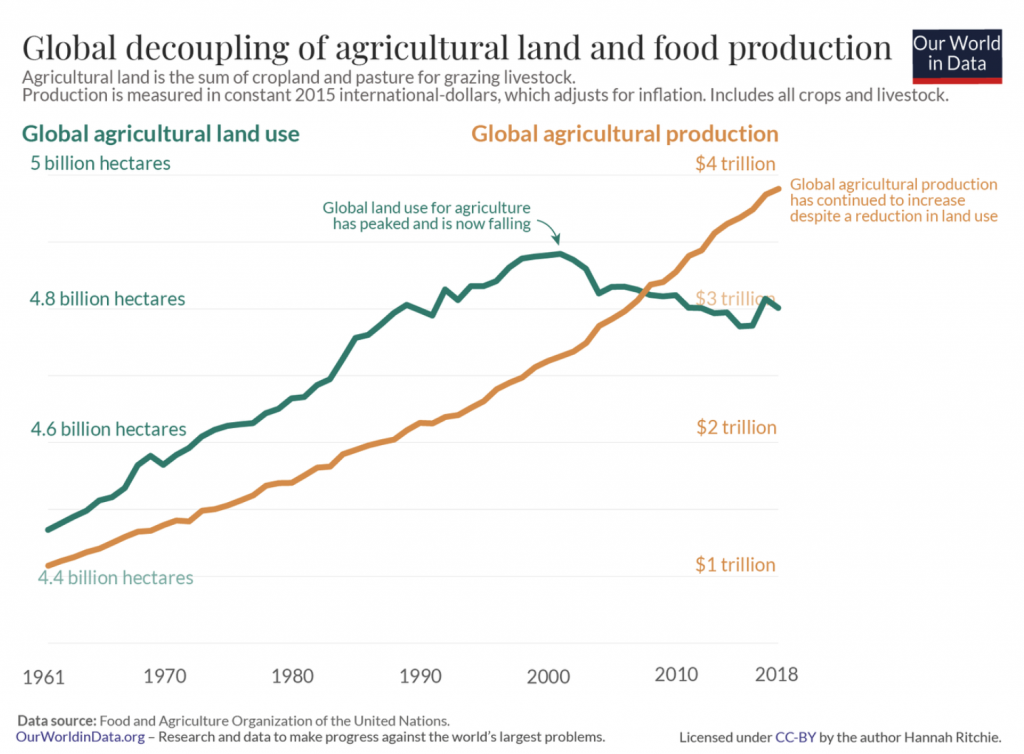

My opinions are based heavily on data from the Our World in Data (OWID) website and the recent book by Hanna Richie, “Not the End of the World” (HB ISBN 9781784745004). The book has an optimistic view of the evolution of global food production and the progression of world hunger and malnutrition, stating: “In the 1970s, around 35% of people in developing countries did not get enough calories to eat. By 2023 this had fallen by almost two-thirds to just 13%”. The reason why a growing world population is now better fed, are technological developments in food production. Richie describes the work of Norman Borlaug in developing cereal crops adapted to the conditions of different regions of the world, as well as the work of Haber and Bosch towards fertiliser developments. She explains that the world arrived at peak agricultural land use around the year 2000 while increased crop yields ensured that global food production is increasing at an accelerated rate, as shown below.

Evolution of global agricultural land use and global food production (from OWID)

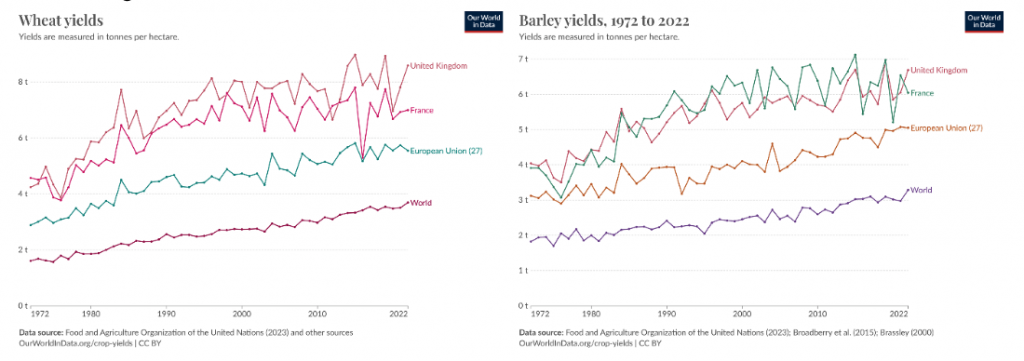

The figures below gives details of wheat and barley yields from 1972 to 2022 for the UK, France, EU and World. All curves show large increases over the 50 year period without indications of yield reductions due to climate change.

Wheat and Barley yields from 1972 to 2022 for UK, France, EU and World (from OWID).

A very unfortunate feature of the Alder paper is that the references are incomplete with no journal details or hyperlinks. Google Searches are required to find the papers and this process often leads to multiple possible sources or failure, always it requires a significant effort to find the intended source. This lack of easily accessible references makes properly understanding the arguments in the paper problematic.

Climate Change and Global Food Supply

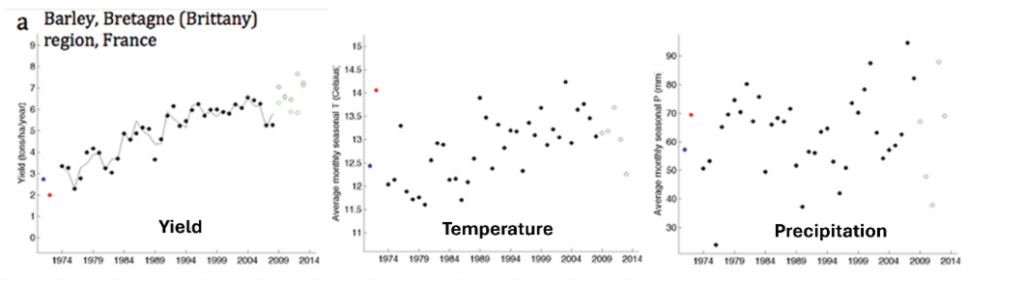

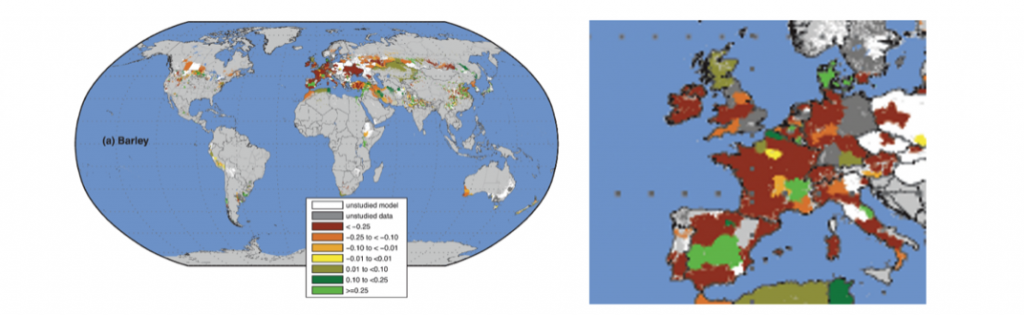

The justification that climate change affects global food supply are only briefly presented and the most important source is reference 10, which (using Google) is: Deepak K. Ray et al.,https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217148. The Alder paper only gives the conclusions of this paper withno description of how the obviously increasing crop yields shown above, are interpreted into reductions due to climate change. In the following I attempt to interpret this Ray et al. paper as a non-expert. The paper takes crop yields for 10 major food sources, together with temperature and precipitation data for 20000 separate regions around the world and makes a complicated analysis to extract the change in crop yield due to climate change for each of the regions. The plots below show one example for the region of Britanny in France, giving the input data in the fitting procedure. The analysis uses a 15-parameter fit to extract the climate change effect. In this particular example, where the actual yield increases more than a factor 2 over 30 years, the analysis concludes that climate change reduces the barley yield by 9%. It is difficult for a non-expert to see how.

Example input data for the analysis of barley yield in Brittany. Year by year yield, temperature and precipitation. (From Ray et al).

The plots below show the results for the 20000 regions analysed for the whole globe and for one of the 10 crops considered: barley. The yield reductions calculated in the analysis are up to 20% in some regions of Europe, while other regions have increased yields. In the plot brown/red colours indicate yield reductions and green indicate increases while grey/white areas are not analysed.

Impact of climate change on barley yield (tons/ha/year). In the 20000 political units analysed. Right global regions analysed and right a zoom on Europe. Brown/red colours indicate reductions in yield and green colours indicate gains in yield. Grey and white area are not analyses. (From Ray et al.).

The conclusion of the Ray et al. paper contains the sentence: “Although recent climate change has likely reduced overall consumable food calories in these ten crops by ̴1% (or ̴ 0.5% across all food calories), there is much variability among crops and regions”. In the Alder paper this conclusion is made more definitive with the sentence: “The average reduction is 1% and the impact is greatest in Europe, Southern Africa and Australia”. Even taking the paper results at face value, a global average of 1% taken over large positive and negative variations, does not seem very significant. Again, I find it impossible to understand how the analysis in the extracts reductions from the obviously increasing yields.

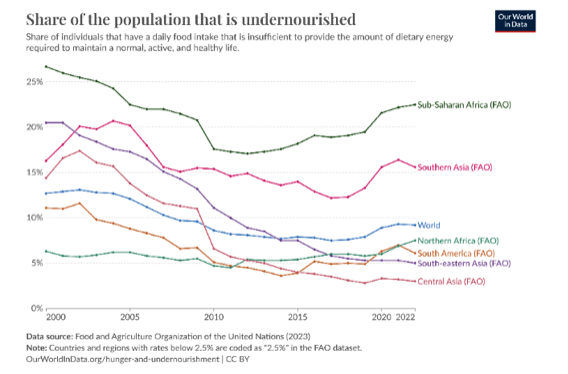

The Alder paper refers to a UN report, saying “climate change will accelerate the rate of food shortages”. This is obviously a statement which deserves extensive justification. Our World in Data and the book by Hanna Ritchie cover this issue and the figure below shows the share of the world’s population that is undernourished. There are large variations from region to region and the in Sub Saharan Africa the situation is getting worse while on average globally the situation is getting better. There must be more factors beyond climate change in this story and it requires much more than a single sentence to explain it.

Share of the population that is undernourished (from OWID).

The statement: “Spain is vulnerable as two-thirds of the country could be severely affected by increasing desertification and soil erosion” is incredibly surprising and certainly requires a reference with a discussion.

If these remarkable claims about a climate change influence on global food production are retained in the paper, I recommend that much more detail is included to justify their validity. These details should include a clear explanation of the methods of the Ray et al. paper. It seems imperative to include a summary of the relevant opinions in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report which is tasked to survey all relevant literature on the impacts of climate change.

UK Agriculture and Climate Change

In the first paragraph of this section, the important point is made that the IPCC AR6 WG1 report clearly says that there is no evidence for changes in extreme weather. Then the second paragraph mentions several diverse examples of extreme weather. The events mentioned are clearly just normal fluctuations and there seems no point in presenting them. The third paragraph discusses modifications to the Gulf Stream, which is a common climate alarmist scare. If this is presented in the paper there must be a clear reference and explanation of the claims being made.

The section, Factors affecting Future UK Food Production, expresses great concern about the reduction in UK agricultural land and the increasing population. These concerns should be seen in the prospective of global agricultural land use per capita which has been decreasing for many decades, in 1960 it was 1.4 hectare per person and in 2023 it was 0.6 hectare per person.

The section, Land use for Food Production, presents losses for particular types of agricultural land and for particular recent years but in a way which is quite a jumble. Some of the numbers seem to be guesses. It isfar from a systematic study and this is admitted with the sentence: “An analysis of land use is complex but there can be no doubt that the area of land for food production is diminishing at a significant rate”. I am definitely left in doubts after reading this section. Given the importance to the arguments of the paper much more clarity is required.

Using UN FAO data via the OWID website, allows a more systematic picture of changes in agricultural landuse. The figure below shows the reduction in total agricultural land use since 1960 for the United Kingdom and includes France as a reference example. The amount of land used for agriculture in France has decreased by 17% in the past 60 years while for the UK the reduction is lower, at 11%, with the data actually showing an increase of 3% between 2011 and 2021. The area of agricultural land use of France, as well as of many other countries, is decreasing so it is clear that the decrease in the UK is nothing unusual.

Area of agricultural land in UK and France since 1960 (UN FAO data from OWID website).

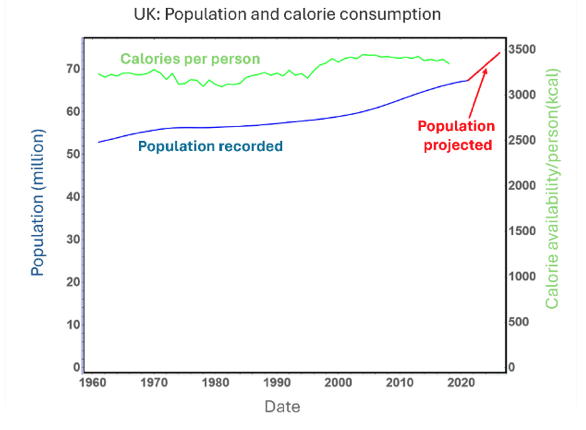

The section, UK Population Growth, quotes numbers for the evolution UK population with projections fora large increase in the near future. From data on the OWID site, the UK population has grown from 53 million in 1961 to 67 million in 2021 as shown in the figure below, an average increase of 0.2 million per year on average over this period. The Alder paper suggests the population will grow 10% between 2021 and2026, an increase of 1.3 million per year, implying the increase will be due to immigration. This projection seems exceptional and ought to be checked. The figure below also shows that the calories available increased from 3200 kcal/person in 1961 to a peak of 3400 in 2010 followed by a small decrease. Clearly if this projected population surge becomes a reality it, will require 10% more food from local production or imports to maintain the same level of calorie intake.

UK population and calorie availability per person ( data from OWID website).

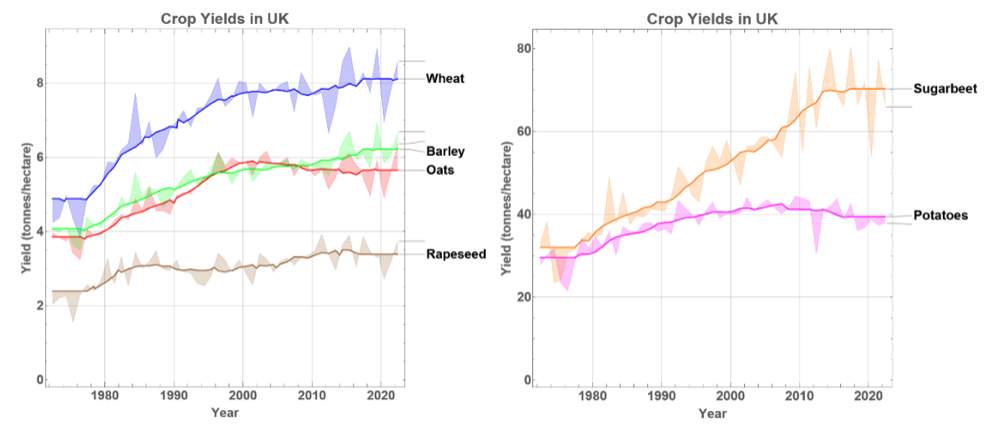

The section, UK Crop Yields, only presents data in tables 4 and 5 for three years. This amount of data is not enough to justify the statements made. The plots below are made from OWID data for 50 years of data. Of the 6 crops shown, 2 (oats and potatoes) show reductions in the past 20 years while the others show increases.

Evolution of crop yield in UK year by year from 1972 to 2022, the thick solid lines are 10 year moving averages. Left Wheat, Barley, Oats and Rapeseed, Right Sugarbeet and Potatoes. (from OWID data).

The statement: “The figures presented clearly show that any loss of production will not be compensated by higher yields”, is, in fact, not demonstrated by the data presented in the Alder paper. It is very unlikely that the century-long improvements in farming technology has ended and it is very pessimistic to say that crop yields will not continue to rise.

Conclusions

The conclusion and recommendation in the paper are restricted to the situation of the UK. I recommend the bulk of the paper is also restricted to the UK situation. It is obvious that different regions of the world have diverse advantages and limitations for food production and in lumping all together in one short paper it is not possible to give complete justifications.

Many of the statements in the conclusion, such as those saying that up to 20% of UK agricultural land could be lost over the next 15-20 years and that the UK production of temperate food could reduce from 75% to 60% or below, are not quantitatively justified in the earlier text. Such dramatic conclusions require better explanations.

Nowhere does the paper mention Brexit. It would be interesting to know in detail how food imports to the UK have been affect by this since 2020.

————

Martin Livermore

An interesting paper and clearly authoritative regarding land use and food production. However, I can’t agree with the conclusion that “…the importation of food will become increasingly difficult due to a number of factors, but primarily the effect of climate change on global food production.”

A point which might be made more explicitly is that, if we truly value domestic agriculture, the balance of policy needs to be shifted away from treating farmers as land and wildlife managers who happen also to grow some food. Also, ‘rewilding’, afforestation and use of land for solar farms need to be balanced against the need to feed ourselves.

Some specific comments:

• Table 2 – Fruit has made a second appearance with livestock production.

• Page 3, Climate Change and Global Food Supply, para 1 – I would suggest an extended session to put climate change in context. The very significant increase in global harvests over the last 60 years has been driven by a combination of plant breeding and improved cultivation techniques, including optimal use of fertilizers and crop protection products. I think it’s fair to say that, although weather patterns clearly have major local impacts from year to year, there is no evidence of any overall negative effect on global crop yields from climate change. Most of the predicted impacts on yield are based on increasingly hot and dry spells in areas that already have high average temperatures and may already be marginal for agriculture. At the same time, it is rare to hear any reference to potential higher yields in northern latitudes. Encroachment on farmland for building, infrastructure etc is clearly an issue and yield increases need to be sought to compensate for this, but there is considerable scope for yield improvements in many parts of the world by improving crop management.

• Page 3, Climate Change and Global Food Supply, para 2 – The University of Minnesota study cited is from 2000; I doubt that there was any hard evidence of an impact of climate change on key crops by the end of the last century and, if this point is to be made, it certainly needs a more recent and authoritative reference. Similarly, the UN report cited is (in my opinion) misleading in concluding that ‘climate change will accelerate the rate of severe food shortages.’ The paper should ideally include here figures for the food calories available globally per capita over the last couple of decades (should be available from the FAO). It is I think generally accepted that most malnourishment is due primarily to a combination of poverty and poor food distribution, rather than insufficient production. Considerable quantities of food are wasted, primarily post-harvest and during storage in poorer parts of the world.

• Page 4, paras 2 and 3 – I understand the point about the potential fragility of some agricultural sectors. I think that the role of government is to reduce the vulnerability of farmers to the vagaries of the weather, irrespective of climate change. Some areas are prone to flooding, some to drought. The reference to the impact on Africa should really be more nuanced. Much of southern Africa suffers periodic extended drought, even before global warming came to be considered a threat.

• Page 4, UK agriculture and climate change, para 2 – I don’t like to see a January day described as the ‘hottest’, a trend that has been encouraged by the climate change lobby. I would prefer to see ‘warmest’.

• Page 4, UK agriculture and climate change, para 3 – The slowing of the Gulf Stream as mentioned in the NFS report is something that was mooted some years ago, but I think has been essentially discredited as a possible occurrence in the medium term (needs checking with recent studies).

• Page 8, last para of Agriculture research section – ‘genetic modification’ is increasingly being supplanted by more precise tweaking using CRISPR-Cas9. One of the (currently few) advantages of Brexit is that we are able to exploit new technology without the likelihood of it being severely hampered by the EU’s use of the Precautionary Principle.

————-

Simon Clanmorris

Summary

It is not clear whether the summary is a summary of this , the Alder paper, or a summary of the GFS paper. I presume that it is a summary of the GFS paper since it states that importation of food will become more difficult because of climate change. The evidence of course points the other way. Temperatures have risen over that past 10 year and so has production of wheat, corn (maize) rice and fresh fruit (see attachment). Indeed Alder acknowledges this in the penultimate paragraph of page 3.

The existing Summary needs replacing with an Executive Summary based on Alder’s work. The decrease in available land (for example) needs highlighting right at the beginning. Many people only read the Exec Summmary.

Climate Change and Global Food Supply

Page 3 I would omit the paragraph about The University of Minnesota report that the top 10 crops are projected to decrease and that ‘ climate change has already affected production’ . Actually production has increased as Alder acknowledges in the preceding paragraph.

UK Agriculture and Climate Change

There is a conflict between para 1 which states that there is no evidence of increased extreme weather and the statement that the Met Office stating that there have been extremes. Paul Homewood would not agree with the Met Office.

I would also omit the speculation about the Gulf Stream. A paper is always more effective if it keeps to facts

Page 4 final 2 lines: a URL is needed for the reference to DEFRA SP1104

Page 7 para 4 There is no evidence so far that climate change has affected the countries we import from. In general CO2 has produced greening.

Page 8para 5 A full URL reference is needed to the WEF 2021 source stating that a 1% increase in carbon stocks would capture more than the total annual fossil fuel emissions. (BTW what is included in ‘carbon stocks’)

Page 9 This is a blank page

Page 11 Some abbreviations are clearly missing. There are no abbreviations after NFS. ONS NPPS RULF UKFSR UAA are missing and there may be others that I failed to pick up.

———–

William Bates

Any use of the term ‘food security’ should quickly answer the question, “Food security for whom?”

The rich have always had food security, even when the peasants have no bread.

The word only appears once in the paper, but I caution anyone writing about food security to avoid using ‘calories’ as metric. Custodial institutions of various types — asylums, prisons, schools, Indian reservations — notoriously economize by providing cheap carbohydrates, ‘empty calories’.

I agree with some of the other commentators: the policy discussion to have should be about UK agriculture as industry.

Global warming has two obvious benefits for agriculture. First, it has increased the length of the growing season, at both ends.

Whatever its case, higher CO₂ is well known to benefit plant growth. Commercial greenhouses find that doubling the ambient CO₂ level (to, say, 700 to 800 parts per million) makes a significant and visible difference in plant yield.

I personally believe that the increase in CO₂ in the atmosphere is a result of the Modern Warming, not its cause.

On certain types of (C3) plants, 800-1,000 ppm can increase yield between 40% and 100% percent.

It’s always possible to have too much of a good thing; but the toxicity limit is around 1,800 ppm.

A recent paper (in a long list) on climate change and agricultural productivity topic is (Chen and Sun, 2024). They found that improved crop yield in China is best explained, out of many factors they considered, by local air temperature and CO₂.

Warmer air has the potential change precipitation patterns in ways that may not beneficial to agriculture — too much or too little — but I think the jury is still out on this.

Every country values some level of self-sufficiency in agriculture. Food supply can be a defense issue, as it was for the UK in WW1 and WW2: the “Victory Gardens.”

But since the UK became a trading nation, it’s been importing food. It started with spices, moved to sugar and tea, then onto the New Zealand lamb in the Commonwealth era.

Now it’s Holland. The Netherlands is the size of the US state of Maryland, but the dollar value of its agriculture exports are second only to the US.

So raw farmland is not a great measure. We should also note that the competition for UK land comes from new housing, which the UK desperately needs, and rewilding, which most would support if done without coercion.

Finally, the author makes a passing reference the UK’s dependence to soya imports from the US and Brazil. That soya is going to feed livestock, not humans, unless Britons have started eating a lot more veggie burgers and tofu since by last visit. If the author thinks people should eat less meat, a defensible position, he should say so.

Soybeans fix nitrogen, a good thing. As for Brazil, its soy revolution came about not by burning down rainforest, but by a genetically altered cultivar that could be grown on the scrub-like Cerrado savannah. The scientists won the 2006 World Food Prize for it.